Productized Mass Timber: Kits, Shafts, and Schedule Wins with Michaela Harms of Sterling Structural

If you were told that a building material could be manufactured at the pace of a car assembly line—one structural panel every 65 seconds—would you believe it?

For decades, the construction industry has accepted the slow churn of concrete pours and steel fabrication as the cost of doing business. Yet, a quiet revolution is underway, challenging not just what we build with, but how we conceive of the entire construction process.

This is not a story about novelty or greenwashing. It’s about a fundamental rethinking of supply chains, project delivery, and the relationship between forests and cities. As Michaela Harms puts it, “We can always be meeting the demand. We have high capacity.” The rise of mass timber, and the modular, productized approach behind it, is forcing architects, engineers, and builders to reconsider what’s possible when efficiency, sustainability, and scale are engineered into the DNA of a material from the forest floor to the jobsite.

The Rise of Mass Timber: A New Era in Construction

Few materials have disrupted the construction landscape as rapidly as mass timber, yet its ascent is rooted in more than environmental ambition or visual appeal. The adoption of engineered wood signals a fundamental rethinking of how buildings are conceived, assembled, and valued.

Michaela Harms , VP of Mass Timber at Sterling Structural , embodies this shift—her trajectory from sustainable building research in Finland to overseeing the world’s largest cross-laminated timber (CLT) operation illustrates the material’s global momentum.

“I really focused on sustainable building... and really a lot of focus on wood,” Michaela recalls, reflecting on her formative years in Finland, a country with a deep tradition of mass timber innovation. This foundation has informed her leadership at Sterling Structural, where she has guided the company’s rapid expansion to meet surging demand. Mass timber’s rise is not just a matter of substituting materials; it is reshaping the industry’s operational and cultural DNA.

Action Step: If you’re new to mass timber, treat it not as a boutique material but as a mainstream building system. Look for partners who can show both successful projects and domestic production capacity.

Efficiency Meets Demand: The CLT Approach

While construction projects are often plagued by delays and inefficiencies, Sterling Structural’s CLT production model has upended expectations for speed and precision. The facility’s ability to produce a CLT panel every 65 seconds is not a marketing boast but a logistical reality, achieved through tightly integrated manufacturing processes.

“We can always be meeting the demand. We have high capacity.” — Michaela Harms

This production efficiency enables not only rapid project delivery but also significant reductions in material waste and labor hours. By standardizing repeatable elements, Sterling has made mass timber a practical choice for projects with aggressive schedules—an achievement that directly addresses one of the industry’s most persistent pain points.

Action Steps:

- Developers → Ask manufacturers about throughput capacity and delivery reliability.

- Engineers → Design repeatable modules/grids to reduce CNC/fabrication time.

- GCs → Don’t assume smaller panels mean slower installs—installers report the opposite once rhythm sets in.

Overcoming Skepticism: The Case for High Volume Production

Doubts about the feasibility of high-speed, high-volume CLT production were widespread when Sterling Structural first proposed its manufacturing targets. Industry partners, including equipment suppliers, questioned the rationale for such capacity.

Michaela recounts, “When we contacted Minda about making our presses... they were like, ‘Why? No one would ever need that much CLT.’”

Sterling’s results have since provided a clear answer. By demonstrating that mass timber can be produced at industrial scale, the company has lowered barriers to entry for developers and contractors, driving down costs and expanding the material’s reach.

Action Step: Ask suppliers about their production capacity and delivery reliability—how many panels they can produce in a given time and how they ensure trucks arrive on schedule.

The Power of Partnerships: Building a Collaborative Ecosystem

The complexity of mass timber projects demands a level of coordination that extends beyond the factory floor. Success hinges on early and sustained partnerships among general contractors, material suppliers, and design teams.

“Partnerships are really what I’m learning are everything in this industry.” — Michaela Harms

Sterling Structural’s collaborative model has enabled faster decision-making and more agile problem-solving, reducing friction across the supply chain. By aligning stakeholders from the outset, the company has created a feedback loop that accelerates innovation and ensures constructability.

Action Steps:

- Involve installers when evaluating panel sizes and crane logistics—their experience confirms smaller, repeatable panels can speed up schedules.

- Confirm glulam and connector lead times before finalizing schedules.

- Favor turnkey approaches when possible—GCs respond better to bundled solutions.

Designing for the Future: Embracing Hybrid Structures

As mass timber gains traction, project teams are increasingly exploring hybrid systems that combine timber with steel to optimize performance and cost.

“If we’re really talking about optimization... sometimes mass timber doesn’t make sense in certain spots.” — Michaela Harms

Hybrid structures allow designers to leverage the strengths of each material, tailoring solutions to the unique demands of each project. This flexibility broadens the applicability of mass timber, making it viable for a wider range of building types and performance criteria.

Action Steps:

- Use CLT where speed and repeatability matter most (e.g., decking).

- Where wide-flange steel outperforms glulam on cost or span, pair steel with CLT instead of forcing an all-timber solution.

- Treat hybridization as a mainstream strategy, not a fallback.

A Sustainable Future: Connecting Forests to Markets

The viability of mass timber is inseparable from the health of the forests and economies that produce it.

“Markets are what incentivize the management of forests.” — Michaela Harms

For Michaela, that means pushing designers beyond a single-species mindset. “Spruce Pine Fir South and Eastern Hemlock may have lower design values, but all of them work if you design for them,” she explains. “If you design your entire building for Douglas Fir panels, you’re locking out other regions—and their mills—from participation.”

The implications are both environmental and economic. Without demand, local sawmills close—even in the middle of a timber boom. By specifying for abundant regional species, architects and engineers can not only reduce procurement risk but also keep forest economies alive. “Maybe you need to design your grid for a spruce pine south panel first,” Michaela notes. “You can optimize later, but start with what’s available in your region.”

Action Steps:

- Ask suppliers which species and sawmills they source from.

- Design grids that accommodate multiple species (SPF-S, eastern hemlock, SYP).

- Treat regional sourcing as both a sustainability practice and a way to strengthen local economies while reducing supply risk.

Conclusion

The conversation with Michaela Harms makes one thing clear: mass timber’s future isn’t about chasing novelty—it’s about scaling smarter. From Sterling’s ability to roll out a panel every 65 seconds, to installers discovering that smaller, repeatable panels actually speed schedules, to the industry’s embrace of hybrids and regionally sourced species, the throughline is optimization. Efficiency, collaboration, and local markets aren’t side notes—they’re the foundation of making timber mainstream.

Michaela’s perspective bridges the forest, the factory, and the jobsite. She shows that capacity matters as much as design, partnerships matter as much as product, and sourcing decisions ripple far beyond procurement. For architects, engineers, and developers, the lesson is simple: the more we align design choices with manufacturing realities and forest health, the faster mass timber can scale into everyday construction.

👉 If you want to go deeper, we pulled Michaela’s top 10 lessons into a quick-reference tool for AEC and developer teams.

.png)

Tired of Mass Timber Challenges Derailing Your Projects? Learn How to De-Risk & Deliver Them.

Lead mass timber projects with confidence — and leave delays, redesigns, and budget blowups behind.

✅ Solve early-stage design, sourcing, insurance, permitting, code & cost hurdles before they derail your project.

✅ Find technical answers on design, detailing, procurement, embodied carbon ROI, hybrid systems & more.

✅ Build relationships with developers, GCs, architects, and engineers shaping mass timber’s future.

Get your ticket— and get the insights, skills, and network to deliver mass timber projects successfully.

Latest episodes

%201.jpg)

This Patented Technology is Upgrading Wood Construction

How can tiny metal hooks dramatically change construction and the way we build with wood?

Learn more about GripMetal.

In this factory tour, we go inside Nucap Industries in Toronto to get a behind-the-scenes look at a material innovation that’s transforming wood construction from the inside out. After more than 25 years of development, GripMetal is being tested as a way to mechanically reinforce wood, unlocking greater strength, ductility, and fiber efficiency without relying on adhesives.

Think rebar for wood.

In this video, you’ll see:

- How microscopic metal hooks mechanically lock into wood fiber

- Why this technology came from high-performance automotive braking systems

- How it’s already being used in modular construction

- What it could unlock for mass timber systems like CLT, NLT, and glulam

- Why hybrid materials may be the next step for scalable mass timber construction

This factory tour goes beyond machinery and process, it looks at how material science can expand what’s possible in modern construction and mass timber buildings.

If you’re interested in construction innovation, factory tours, or the future of mass timber, this video breaks it down from the ground up.

.png)

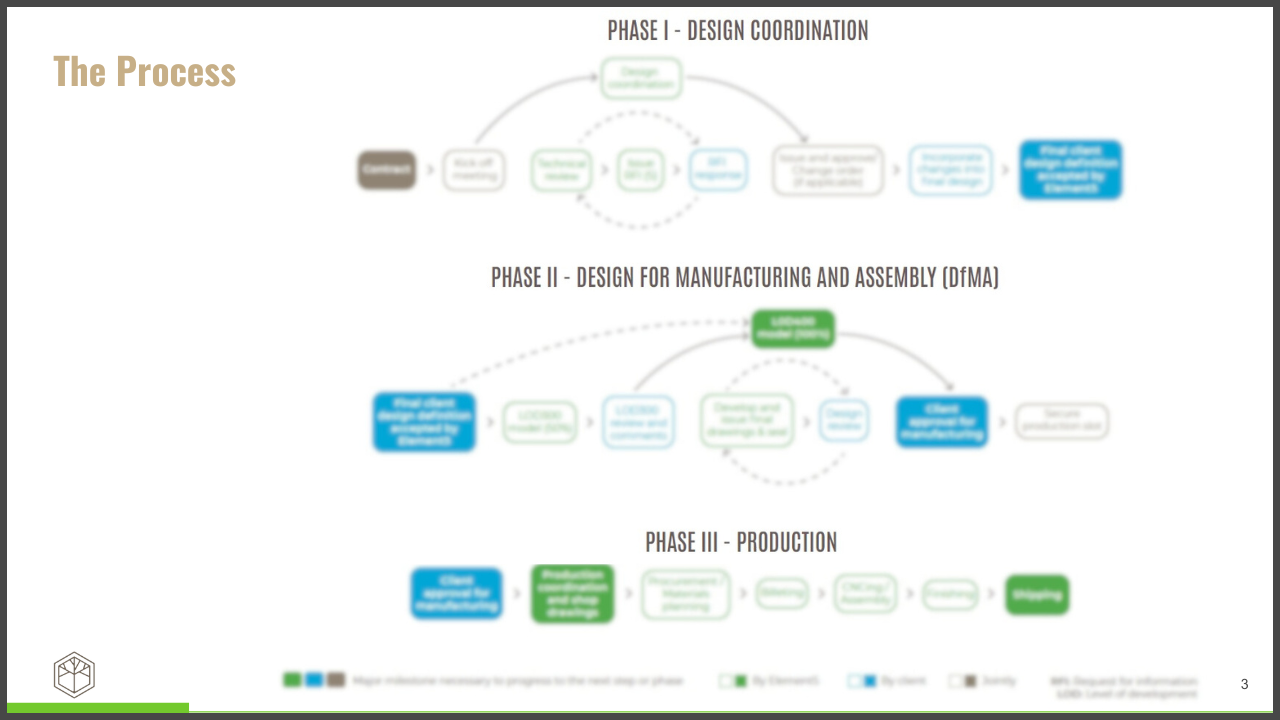

DfMA Explained - Mass Timber Building Success w/ Kevin Rocchi of Element5

It only takes one last-minute shift in structural grid lines—sometimes by a few inches—to trigger a cascade of rework that cripples even the best-laid construction plans. In the world of mass timber, where every dimension must align for precise fabrication, that single tweak can spark confusion with suppliers, drive up costs, and derail project schedules in ways no one expects.

This tension between early design responsibility and chaotic midstream changes is the real fork in the road. If architects, engineers, manufacturers and fabricators understand how their early design process affects the later-stage manufacturing and delivery phases - entire budgets stay intact and installation flows with fewer hiccups. But neglect the Design for Manufacturing and Assembly fundamentals (DfMA) and small misalignments can spiral into endless rework, production fiascos, and lost trust with owners.

Breaking Down the Drawings

The best way to make sure a mass timber design is ready for manufacturing is to pick it apart.

“We really, for lack of a better word, destroy the drawing set. We find all the mistakes. … We need to know all the parts of the drawing, make sure there’s no unknowns.” - Kevin Rocchi , VP of Engineering at Element5 .

That teardown begins with a rigorous, discipline-wide technical review—architectural, structural, and mechanical—hunting for missing dimensions, ambiguous load paths, unclear slab extents, hidden geometry, and any detail that leaves room for interpretation. Kevin’s team at Element5 compiles every gap into a master question list and turns it into a formal RFI. When that first RFI balloons to 20 or 30 questions, it’s often a sign that the project isn’t as developed as the design team may have thought.

One area where designers consistently underestimate the supplier’s needs is load clarity.

It’s not enough to provide general design loads. Mass timber suppliers need dead, live, wind, and seismic loads broken out separately, because they must apply their own load-duration factors (CD in the US, KD in Canada) to each case when sizing connections. If the supplier doesn’t know the breakdown between dead and live loads, they can’t apply the correct load-duration factors—and any resulting connection capacities become unreliable.

That same need for clarity extends to diaphragm and lateral design. Suppliers need to see the complete lateral load path—shear diagrams, load levels, and the specific shear-resisting elements—so they can determine the correct connection forces. Without that information, they’re forced to reverse-engineer the lateral system from the drawings.

When the design team doesn’t supply the necessary load breakdown, Kevin provides the connection capacities he can justify using clearly stated CD/KD load-duration factors. He then sends those calculations back to the engineer of record with a simple request: Confirm that this capacity works for the loads you intended. It’s a back-and-forth cycle that drains time and invites rework.

The Big One — Shifting Grid Lines

Among all the coordination challenges that derail mass timber projects, one consistently stands out.

“The big one for me is for architects… lock in your grid lines… Don’t change your grid lines once you know the mass timber supplier is engaged.”

A locked grid is the foundation for millimeter-accurate fabrication. Every glulam beam, every CLT panel, every connection detail depends on the final geometry. Shifting a column, adjusting an overhang, or nudging a bay after supplier award forces the manufacturer to re-model, re-coordinate, and re-issue shop drawings—all while the structural engineer and architect revise their own documents. It’s a cascade of new RFIs, conflicting markups, schedule drift, and preventable cost escalation.

But Kevin adds an important nuance: there is a phase where some flexibility is appropriate.

During DD, before supplier selection, it’s reasonable to keep the grid flexible and “supplier agnostic,” especially when different suppliers offer different glulam widths and depths. Every manufacturer uses its own standard sizes. Instead of locking a specific beam width prematurely, Kevin advises design teams to:

- Centerline beams and columns, and

- Accept that final beam widths and depths may shift ±½ inch once a supplier is chosen.

This approach preserves optionality without creating downstream chaos.

CLT brings its own considerations. Designers often attempt to optimize panel thickness by specifying thinner lamellas—hoping to reduce weight or material. But North American mills overwhelmingly produce standard 38mm 2x stock, and thinner lamellas require suppliers to plane down higher-grade material, wasting fiber without reducing price.

“It’s literally the same price for us to sell you a 175mm as it is for a 139mm,” Kevin noted.

Instead of trying to fine-tune lamella thicknesses—which rarely reduces cost and often increases fiber waste—design teams should focus on defining top-of-slab elevations early and leave the selection of lamella configurations to the supplier once they’re engaged.

Once the supplier is engaged, however, the grid must stop moving. Any shift reverberates through fabrication modeling, engineering checks, hardware sizing, panelization logic, and connection detailing. What looks like a harmless tweak on paper is, in practice, a design reset.

What Happens After the RFI Cycle

Once Element5 has enough RFI responses to lock in slab extents, grid lines, and design loads, the work starts to shift from design coordination into fabrication. At that point, the supplier begins building the manufacturing model—the digital source of truth that drives CNC production, hardware procurement, and shop drawings.

Element5 creates that model in SolidWorks, not Revit. “We model it in SolidWorks to the millimeter,” Kevin said. SolidWorks is where the exact fabrication geometry is defined: every notch, seat, hanger, bolt, screw, pocket, and tolerance needed for machining and assembly. Once this level of modeling begins, even small design changes ripple through the production workflow.

As that model develops, Element5 issues a confirmation RFI to align the design assumptions with what they’ll actually supply. That RFI typically verifies:

- Glulam grades

- The glulam widths and depths Element5 will use

- CLT grades and layups

- Final CLT panel thicknesses

- Any differences between the design team’s assumed member sizes and Element5’s standard dimensions

Even with a detailed drawing set, the supplier has to re-baseline the exact sizes and grades they intend to fabricate, so design teams should expect this step.

Once the SolidWorks model is defined, it’s exported to Rhino and then into Revit to create the Issue for Approval (IFA) drawings. The IFA set shows what Element5 intends to deliver: the member sizes, panel extents, and connection details that have been thought through to the millimeter.

From there, the approval loop is straightforward but important: Approved, Approved as Noted, or Revise and Resubmit. A clear, timely review at this stage keeps engineering, procurement, and production aligned.

After the IFA set is approved, Element5 moves into full detailing—modeling every component to the millimeter, finalizing custom steel, completing fastener takeoffs, and batching panels and beams by truckload to match the planned erection sequence. At this point, the digital model isn’t just documentation; it becomes the playbook for how the building will be cut, shipped, and assembled.

Coordinating the Jump From Factory to Jobsite

Coordination with the general contractor and the installer is just as critical as the design itself. The goal is simple: ensure the building goes together on site as smoothly as it was modeled.

Mass timber installation lives or dies by sequence.

Panels and beams aren’t generic two-by-fours dropped on the ground in a bundle—they arrive CNC-cut, connection-ready, and staged for a specific order of assembly. That’s why Element5 plans material by the truckload.

“If seven panels fit on a truck, those seven panels are going to be batched together,” Kevin explained. “We need to know—are you picking panels directly off the truck and installing them right away, or are you unloading them to the ground first? That completely changes how we stack the load.”

If the installer plans to “pick from the truck,” panels must be stacked in reverse installation order, with the first piece needed sitting on top.

If the contractor is offloading everything first, the batching strategy changes again.

Ignoring these logistical questions can force the install team to reshuffle entire truckloads manually—costly, slow, and unnecessary. A single quick response from the on-site team (“Yes, we’re picking from the truck” or “No, we’re staging first”) can save hours of site labor and prevent sequencing mistakes that ripple through the build.

This is why communication during this stage carries so much weight.

Kevin put it plainly: “Coordinating it with the general contractor and installer is key to the process.”

Just as delayed RFI responses earlier can hold up modeling, late answers at this stage slow procurement, slow batching, slow shipping, and ultimately slow erection. The supplier is planning fastener orders, custom steel lead times, and CNC operations around the sequence communicated by the field team. Any ambiguity introduces friction.

The more the GC and installer stay in sync with the supplier at this point—confirming crane plans, pick-from-truck strategies, erection pacing, and site constraints—the more the mass timber package behaves the way it was engineered to: predictable, efficient, and dramatically faster.

How Element5 Is Raising the Bar in Manufacturing

Successful projects are always Element5’s priority, and behind the scenes, Element5 is quietly retooling their operations for more mass timer success in North America.

After a recent investment from HASSLACHER NORICA TIMBER, now a majority shareholder, Element5 has added a new glulam production line based on Hasslacher’s line in Europe. This new line became fully operational this past September and is capable of producing roughly 50,000 m³ of glulam per year, freeing the existing line to focus on CLT only at a capacity of 50,000 m³ as well . That separation of lines reduces the constant trade-off between CLT and glulam runs and gives project teams more predictable capacity.

The new glulam line is part of a large expansion to the overall facility. On top of doubling production capacity, the expansion doubled the size of the plant from 130,000 square feet to over 350,000 square feet, including a new 2-storey mass timber front office.

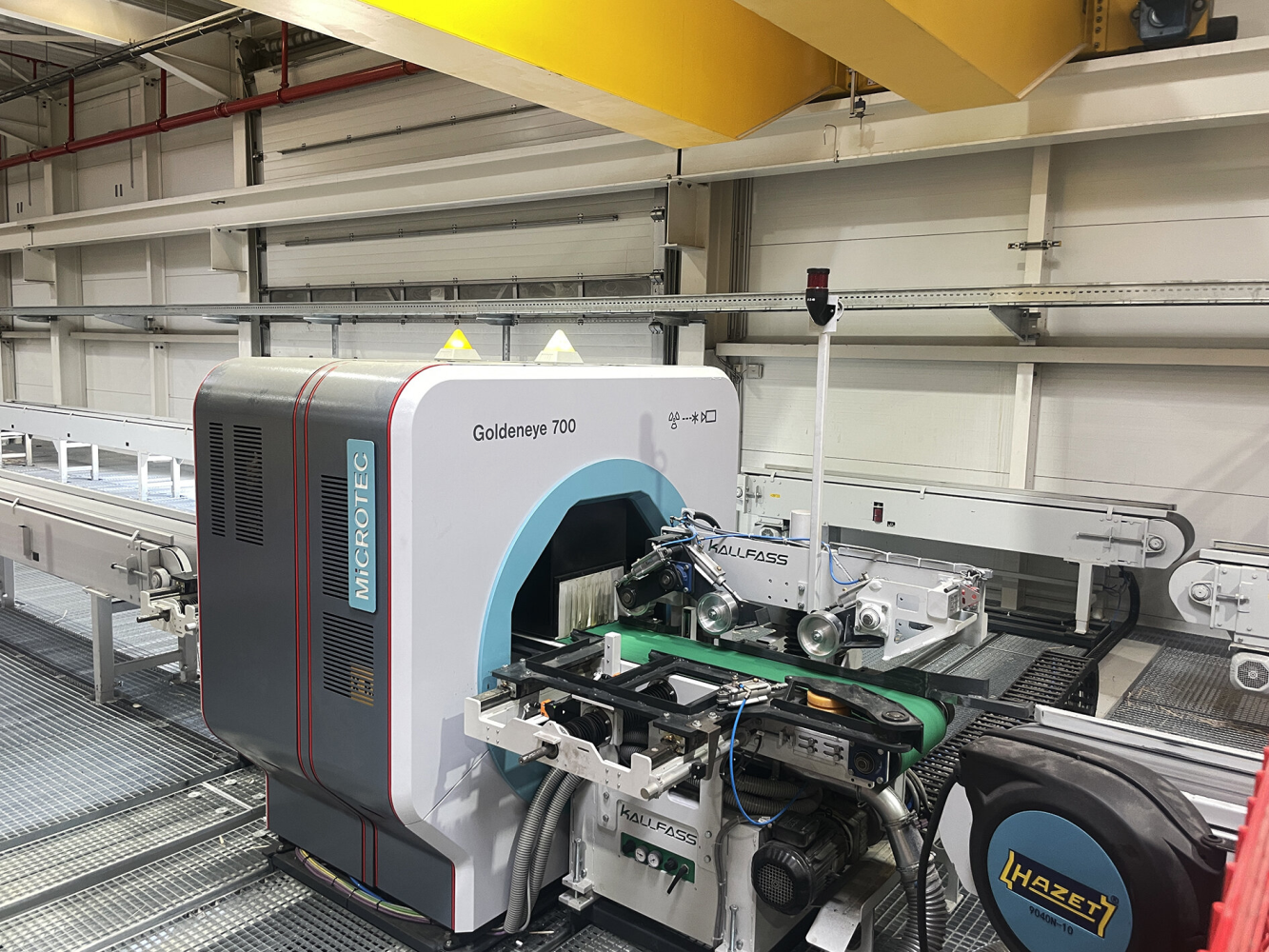

On the CLT side, Element5 has already expanded its CNC and value-add area and completely rethought panel handling. Historically, CNC was the bottleneck: every panel had to be picked up by crane, machined, then moved again. Today, panels move on conveyors through three CNC machines in a continuous flow.

As Kevin put it, that shift “moved our bottleneck back to production”—a good problem to have.

The result is faster, more consistent machining and less risk that CNC capacity is what holds up your schedule.

Element5 has also built a dedicated sorting and grading building around a MiCROTEC© Goldeneye scanner. Instead of 10–15 people visually grading 2x material, lumber now runs through the scanner, which measures moisture, stiffness (MOE), dimensions, and defects board by board. Wet pieces are diverted to the kiln; higher-strength boards are sorted into stronger categories; localized defects can be cut out so the remaining piece qualifies for a higher grade.

As Kevin put it, the system “essentially allows you to make MSR out of everything,” and he’s blunt that traditional visual grading is outdated by comparison.

On top of that, Element5 is working with several Canadian partners to develop new glulam grades using “remanufactured lamellas”—homogeneous beams that are ripped, rotated, and re-laminated so defects and finger joints are staggered in the tension zone.

Those beams are slated to be tested at the University of British Columbia, with the aim of establishing design values for future CSA O86 updates. The goal is straightforward: to enable, for the first time, spruce–pine–fir glulam produced this way to exceed 2,400 psi allowable bending strength—reaching the 24F–1.8E performance level designers typically associate with Douglas fir.

For project teams, all of this adds up to tangible benefits:

- More reliable capacity and lead times as CLT and glulam get their own dedicated lines

- Faster, less fragile CNC flow thanks to conveyor-based handling instead of crane moves

- Better use of the fiber basket, with machine-graded lumber and upgraded boards replacing broad visual buckets

- Higher-performing glulam options from SPF previously only available with Douglas Fir.

Conclusion

Mass timber succeeds when everyone upstream and downstream is aligned. Clear drawings, locked grids, fast RFI cycles, tight modeling, and real-time coordination are what turn a good design into a smooth build. With Element5 advancing both its manufacturing capabilities and its project delivery process, design teams have a clearer path than ever to predictable schedules, tighter budgets, and timber structures that come together exactly as intended.

Join Our Newsletter to Download the Project Design DfMA Workflow Diagram from Element5.

Mass Timber Just Got Even Bigger w/ Corey Hokanson of SmartLam North America

Picture a downtown site at dawn, where contractors gently swing a 50-foot-long, 2 feet wide and feet deep timber bream into place. Not for building, but a parking structure.

That’s the reality of what's happening in the world of mass timber right now. And to unpack it, we spoke with the Systems Wizard himself, Corey Hokanson, the Design Manager at SmartLam North America.

An Industry Scales Up: From Mass to Mega Timber

Columns and beams once considered “big” are now growing so large that onlookers knock on them to check if they’re hollow. That’s exactly what happened when SmartLam North America showcased its new 24-inch by 42-inch glulam at a recent conference. They drew immediate curiosity about how glulam could possibly reach such dimensions - and be produced economically. Until recently, achieving a beam two feet wide by up to four feet deep often meant a time-consuming, custom hand-layup process. Now, SmartLam presses in Dothan can turn out these jumbo glulam members seamlessly.

Driving this transformation is a practical desire to manage higher loads and longer spans with fewer pieces, all while addressing fire and sustainability requirements. In Hokanson’s view, “There’s a lot of things that change when you start getting into pieces that big and that heavy.”

One direct technical gain is the potential to reduce overall piece counts—doing away with multiple smaller beams in favor of a single member. Fewer members means fewer connections and labor hours, but it also demands bigger handling equipment and more careful planning. Because single pieces can top 12,000 pounds, oversights in design, sequencing or installation can erode those hoped-for benefits. The industrial leap from “mass” to “mega” marks a moment where “everything has changed in the last couple years,” adding fresh options that simply did not exist at this scale before.

3-Hour Fire Rating: A Bold New Frontier

Not long ago, few imagined that exposed timber could endure three hours of direct fire exposure. Yet Hokanson describes new furnace tests showing mass timber assemblies charring for three hours with “no coatings, no intumescent paint, no drywall wrapping.” During these tests, the timber effectively formed a thick char layer on the surface, protecting an undamaged structural core. He notes, “They put it in a furnace and basically blast it with a blowtorch for three hours… it’s like you threw it in a bonfire.”

From a design perspective, this changes the conversation around heavy timber in spaces that demand ultra-safe, code-driven solutions. It also means teams have a legitimate alternative to expensive encapsulation or the steel and/or concrete typical for high fire-rating assemblies. In tangible terms, using these 3-hour rated timber assemblies frees projects from adding extensive gypsum board or intumescent coatings. The cause-and-effect is straightforward: by allowing enough mass for extended charring, the material retains a stable core, preserves structural performance, and satisfies the code. Hokanson points out the real advantage of timber’s char characteristic: “You figure three hours… that’s a long time… you can get a lot of people, everybody out of a building in three hours.” It’s an endorsement that large wood members are stepping decisively into applications once reserved for concrete or steel.

Podiums and Parking Decks: Challenging Concrete’s Turf

Now, timber can claim spaces long dominated by concrete—like podium levels and parking decks. SmartLam is already fielding designs that swap out concrete beams, slabs, and rebar with 7+ layer CLT and heavy glulam. Hokanson captures the schedule benefit in practical terms:

“I can come drop in these four pieces of timber off the semi-truck in two hours. Or we can sit there and form this all up for the concrete and then put all the rebar in… then we can pour the concrete. Then we can sit around and wait for it to cure….”

That contrast grapples with weeks of site labor, specialized forming and bracing, and the wait time that inevitably follows a wet pour.

Replacing a conventional podium system (concrete beams plus a concrete deck) with large glulam beams spanned by nine-ply CLT does come with its own unique set of consideration, though. Hokanson describes a project employing 12.5-inch-thick CLT panels: “That piece weighs 12,000 lbs.… we better make sure it’s in the right order on the truck,” emphasizing the need for careful sequencing and onsite logistics.

Mastering the Logistics Puzzle

Enormous structural members offer clear benefits, but only if carefully choreographed from manufacturing to final install. It starts the moment a 12,000-pound panel is pressed and ends with that panel being correctly sequenced on-site. Hokanson warns, “If you get partway through putting it together and you’re like, ‘Oh, I should have put that one in first,’ now I got to go pull three pieces out… you’re losing all that time schedule savings.”

A concrete deck might allow continuous pour after pour without worrying about piece-by-piece staging. Timber, however, arrives “basically a puzzle piece,” so just-in-time sequencing is crucial.

The upside? Mastering that puzzle yields an impressively streamlined crew—“on a mass timber install, you might have five or six people,” Hokanson notes. With fewer trades on-site, the risk of coordination clashes drops. But to keep that advantage, each piece must arrive when needed and in the exact orientation for rigging and lifting into position. For those tackling a podium job or large commercial floorplate, the short yet precise staging can be a major edge—provided the entire supply chain works in lockstep, from the press operator in Dothan to the crane operator on the job site.

The Four-Foot Screw: New Realities for Field Install

Hardly anyone expects to drive a four-foot screw into solid wood, but the new wave of massive beams demands equally massive fasteners. “You’re not going to find a lot of 16-inch screws at your local hardware store,” Hokanson observes. That leads to specialized torque drivers, batteries that can handle heavy loads, and yes, an awareness that if the tool overheats or the screw seizes, installation will be disrupted. “You have to drive it in one go all the way in,” he explains, because if mid-thread cooling occurs, the screw can bind and snap.

The consequences of using the wrong method can be devastating. “Worst case scenario, you’re taking all those screws back out and replacing them all because you voided the warranty… or you broke the screws off,” Hokanson says. In the absolute worst case, snapping a critical fastener inside a beam can require full beam replacement—a cost nobody wants. This scenario flips a standard wood framing approach (laborers with practice at sinking three- or four-inch screws) into a new territory where site managers must plan for specialty equipment, factor in slow-driving drivers, and equip extra drills to cycle in when batteries begin overheating. In short, ignoring the fastener hardware dimension might jeopardize the very speed advantage that large mass timber promises.

Automated Presses Meet Sky-High Loads

No one doubted that big glulam members could be made by hand. But producing them at scale—“a press load of beams every fifteen minutes,” as Hokanson puts it? Utilizing a uniform, factory-tight layup with presses sized for these larger members makes it possible. And more reliable.

Fasteners and connections can fail if there are gaps in the lamellas, something mitigated with a consistently dense beam. Hokanson explains, “Simpson Strong Tie has an actual study and a formula for how much you have to reduce the capacity if there’s gaps between boards,” referencing the risk with hand layup members of this size. The new automated llines mitigate that capacity drop. The result is more reliable performance, higher design loads, and a confidence that timber can compete head-to-head with steel or concrete in major structural roles. As Hokanson says of the new system, “We can make anything in between this and this,” meaning wide, deep, or a combination of both, all without the manual constraints of older methods.

Pushing Off-Site Construction Principles Further

Massive beams magnify a core principle of mass timber: “You really don’t want to have to do that” on site, Hokanson quips when describing the labor of drilling a hole through 42 inches of solid wood. A routine task might become an hour-long ordeal, requiring two people, multiple drill bits, and a shop vacuum to clear sawdust along the way.

The obvious takeaway: incorporate all cuts, holes, and service runs into the CNC stage. “If that shows up in the wrong order and you have to move that somewhere… how do you move that?” quickly transforms from a rhetorical question to a budget-busting predicament.

In a world where beams can approach 4 feet in depth, that coordination starts early and runs deep. Whether it’s a parking deck or an office building with hidden conduit, everything from the largest structural connection to the smallest wire chase needs to be pinned down before the press and the CNC do their work.

Future of Mega Mass Timber

“Don’t assume that we can’t do something,” Hokanson says, stressing that many long-discussed but previously unfeasible mass timber ideas deserve revisiting.

The giant beams are here—and they are more than a novelty. “Everything has changed in the last couple years… we’ve got bigger screws, bigger fasteners, bigger brackets… let’s just do more of it.” Then, with that, he closes the door on doubt and opens it to a new scale of timber.

The Key to Mass Timber w/ Julian Lineham of Studio NYL

Most mass timber failures don’t happen in the field. They happen months earlier—when teams gloss over fire ratings, undervalue acoustic control, or punt connection design down the line. By the time those gaps surface in coordination, it’s too late. Costs climb, schedules slip, and the supposed schedule savings with mass timber starts looking like a liability.

Few know this better than structural engineer Julian Lineham, PE, F.SEI, F.ASCE, CEng, FICE , a founding principal at Studio NYL with more than 20 mass timber projects under his belt. Over three decades, he’s shown that mass timber only delivers on schedule, budget, and design intent when detailing is resolved from the start.

Bespoke Detailing: London’s High-Tech Era

Julian Lineham came of age in London’s late-1980s “high-tech” design scene demanded structural engineers draw every bolt, splice, and rebar layout. That culture of bespoke detailing shaped his entire career. “We literally designed and drew every connection,” he recalls — a discipline that still drives how he approaches mass timber today.

When he moved to the U.S., Lineham was struck by how often structural packages carried less detail than he was used to. Instead of adjusting downward, he doubled down on the UK mindset: every connection documented and resolved . That rigor pays off in mass timber. Clear connection drawings reduce RFIs, shrink field rework, and preserve the architect’s vision — especially if you want the warmth of exposed timber without unnecessary steel dominating the aesthetic.

Connection Design in House: The Fast-Track Ticket

When time is money, outsourcing connection design can derail schedules and compromise aesthetics. Julian Lineham traces this conviction back to his London training: “We literally designed and drew every connection,” he says. That rigor matters even more with mass timber, where nearly every connection remains visible in the finished architecture.

“I like to keep the connection design in-house,” Lineham explains. Delegating to a 3rd party is possible, but, as he puts it, “you lose a bit of time and you lose a bit of the vision.” By managing bearing conditions, plate details, and fastener layouts from concept through construction, Studio NYL avoids the back-and-forth that typically comes with delegated design reviews.

Fire & Acoustics: Resolve Them Early or Pay Later

Exposed timber ceilings bring warmth and character, but they also bring two of the biggest considerations in mass timber: fire ratings and acoustics. Julian doesn’t mince words: “The type of construction and the fire rating is very critical. And then the second thing that’s critical very early on is to look at acoustics.”

Leave those unresolved and you’ll pay for it later. Fire and acoustic requirements set minimum sizes and floor build-ups; miss them early and the fixes show up as deeper members, thicker toppings, or fire protection add-ons at connections—all of which add cost, erode schedule, and threaten the clean timber aesthetic the client expects.

At the North End Community Center, Lineham’s team specified a five-ply CLT panel with an acoustic mat and a 2½-inch topping. That assembly was intentional; it was designed up front to achieve the sound rating without inflating the member depth.

On the fire side, he points out that choosing a slightly wider timber member to provide natural wood cover is often cheaper and faster than trying to fire-wrap steel later. Otherwise, you’re “messing around trying to intumescent paint” steel connectors and columns — a sequencing headache that slows down the job

Bonnet Springs Park: Speed, Scale, and the Power of Repetition

“Speed was essential” at Bonnet Springs Park — a 250-acre reclamation project in Lakeland, Florida, with fifteen new buildings rising on a former railyard. For Studio NYL, it was their first foray into mass timber, and the key was repetition. “There was a very large event center with an 80-foot span,” Lineham recalls, “and we ended up doing that with glulam beams and a CLT roof.”

The structural strategy was simple but deliberate:

- Double glulam beams side by side to reduce roof depth.

- Keep panel sizes repetitive for faster fabrication and erection.

- Use hybrids at the perimeter: CLT panels spanning between slender HSS steel beams and columns, bearing on a bottom plate for a clean colonnade.

Florida’s minimal snow loads made the long span feasible, but the real payoff came in the field: “All the panels were erected in three days… it was a very, very fast project.”

With contractors moving simultaneously across fifteen buildings, the ability to repeat details and standardize panels made the difference between weeks of work and days of assembly.

North End Community Center: Where Hybrid Solves Hard Realities

In St. Paul, Minnesota, Studio NYL teamed up with Snow Kreilich Architects on what would be the firm’s first mass timber project. The program called for a gymnasium with broad spans but columns slender enough to fit a tight urban footprint. “They were interested in exploring [mass timber] with us,” Lineham recalls.

The gym roof spanned 55–60 feet using double glulam beams with five-ply CLT panels above, spaced to match the panels’ capacity. But carrying the entire complex in timber would have meant massive columns that the site couldn’t accommodate. The hybrid solution combined round steel HSS columns, exposed steel brace frames, a perimeter glulam beam, and an interior CMU elevator shaft — each material placed where it made structural and financial sense.

The design allowed the gymnasium to retain the warmth of an exposed timber roof while keeping vertical supports light and efficient. For the client, the choice went beyond performance: “They wanted a mass timber building…to rebuild the community,” Lineham says. Surrounded by timber, occupants gain a welcoming environment that research shows lowers stress and blood pressure.

The project wasn’t without trade-offs — mass timber carried an upfront premium — but as an institutional investment and a civic anchor, the long-term value was clear. Here, hybrid construction solved the realities of site and budget while preserving the architectural vision.

Museum of Nebraska Art: Historic Meets Forward-Thinking Timber

Julian Lineham’s passion for blending new and old is on full display at the Museum of Nebraska Art (MONA) in Kearney. The existing museum occupied a 1911 post office building, and the plan called for both a historic renovation and a new two-story mass timber wing over a basement. “The architect conceived it as a full mass timber building — CLT roof floors, glulam beams and columns,” Lineham explains.

Cantilevers up to 12 feet required glulams nearly 56 inches deep, which conveniently allowed MEP systems to be distributed within the beam depth, leaving the exposed underside clean and gallery-ready. But executing that vision meant balancing code and constructability. Some steel brace frames and integrated steel columns required fire protection, which in turn demanded careful sequencing of intumescent paint so the timber finish wasn’t marred.

Construction during a Nebraska winter added another challenge: snow and moisture management. Crews had to keep CLT panels protected to avoid saturation. Despite the hurdles, the finished project delivers a striking contrast of heritage brick and expansive timber galleries. At the grand opening just months ago, the client was not only impressed by the aesthetics but also thrilled with the expanded capacity to display its collection.

The Next Frontier: Stadiums, Kinetics, and Radical Ambition

Julian Lineham doesn’t see mass timber as limited to community centers or mid-size cultural projects. “I would absolutely love to do a mass timber stadium of any kind of size…that would really excite me,” he says, pointing to examples of entire sports venues built from wood for their natural aesthetics and carbon advantages.

And his imagination doesn’t stop there. A past client once proposed a rotating museum floor that would track the sun. Many might dismiss the idea, but Lineham sees it as a glimpse of where mass timber is headed: a fusion of engineering, kinetics, and mass timber’s surprising adaptability.

That appetite for innovation is what excites him most. New connection strategies, novel panel systems, and unconventional geometries are constantly being tested. Europe has taken the early lead, but in North America, best practices are emerging in real time — fueled by open exchange at conferences and a willingness to prototype in practice. As Lineham put it: “It’s an industry that really wants to iterate and innovate as well.”

.avif)